The How, When and Why of Don’t Call Me Princess

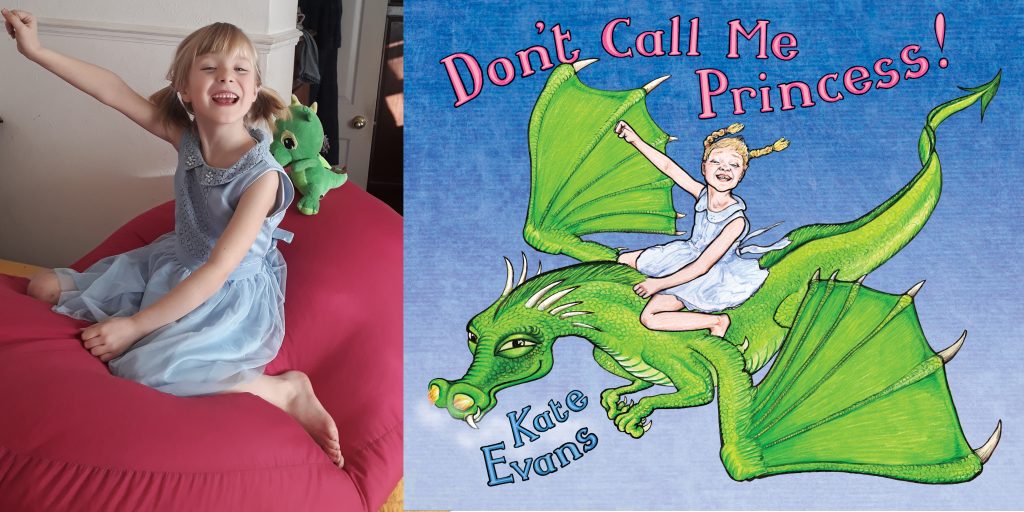

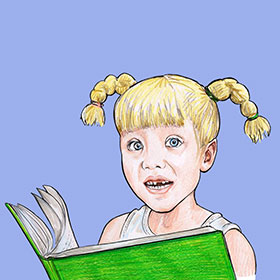

Our story starts, dear reader, about five years ago when my daughter looked like this:

Quite little, huh? And we were in the Sure Start Centre (RIP), at playgroup, and there was a dressing-up box, and she put on a blue shiny dress. You know the sort – the ones the Disney corporation and Tescos punt to our little ones. Whereupon all the other adults in the room exclaimed “Oh! You’re a princess!” “Pretty as a princess!” and I was like:

because I have never liked this princess thing.

We’ve come so far since the 1950’s. Back then girls had such restrictive role models. They could just aspire to be a ballerina, a nurse, or a teacher – all professions which carry a modicum of skill. Nowadays, they get to be princesses. We’ve come so far. In the wrong direction.

I mean, what do princesses actually do? They’re the property of their father, they sit around looking pretty, they become incapacitated as a result of some (usually avoidable) hardship or peril… Then they are ‘rescued’ by a complete stranger who gets their hand in marriage and nicks their kingdom.

That’s the fairy tale version. There are real-life princesses too, and while I follow the reality TV show that is the Windsors as much as anyone else, I’m under no illusions that filling my newsfeed with reports of the state of Meghan Markle’s tights is anything other than self-destructive. The media collectively grooms us into accepting the monarchy, and since most people in the UK believe that the Royal family “deserve” the obscenely disproportionate amount of British land, assets, public funding and political power that they retain, it works. Let’s not think about the fact that if Prince Phillip hadn’t spent £18,690 on a single train trip last year maybe our Sure Start Centre wouldn’t have had to shut down?

From time to time, children’s authors try to reclaim the princess stereotype. They’re good stories. I’m glad that Babette Cole made Princess Smartypants, Munsch gave us The Paper Bag Princess and Kate Beaton dreamed up The Princess and the Pony. But there are a lot of them. A browse of A Mighty Girl’s book catalogue throws up 98 versions of the “independent princess”, suitable from birth(!) to teenage years. I’m not interested in adding to it. Princesses, Kings and Queens have no place in any children’s story that I write. It still plants the idea in young minds that one person can own or run a country and everyone else in it should be subjects, not citizens. I don’t think that’s a good idea. I prefer democracy to dictatorship.

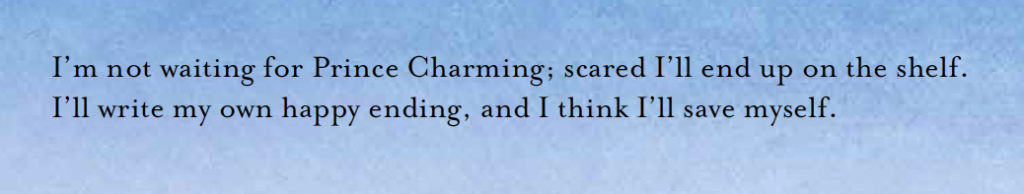

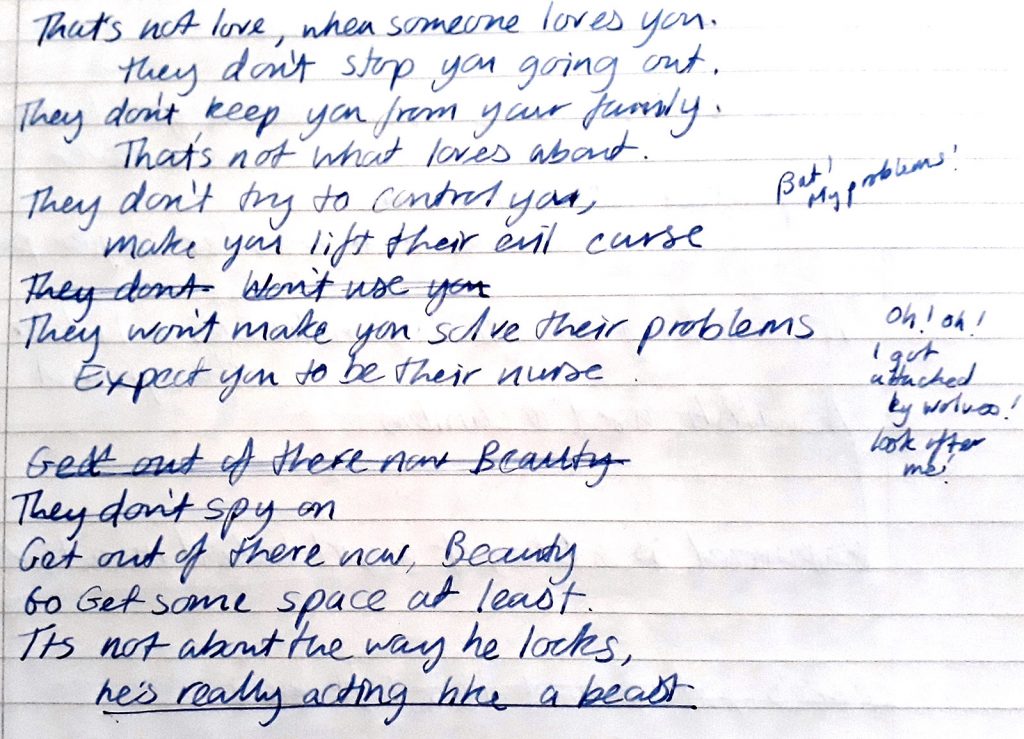

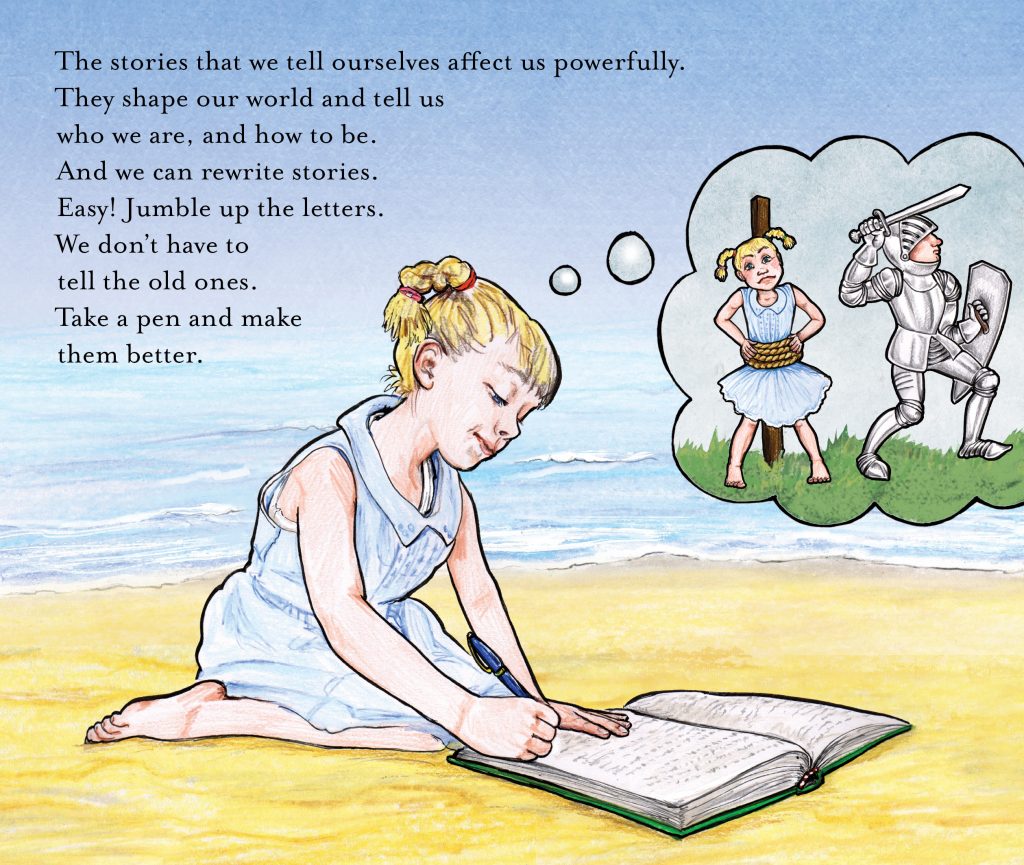

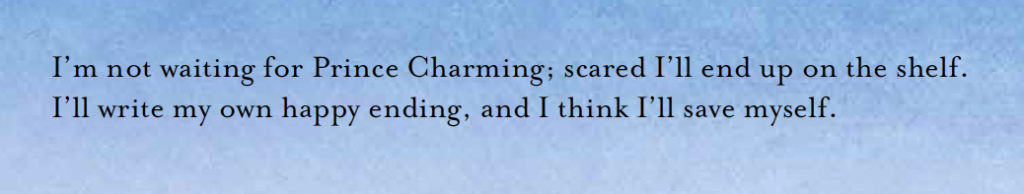

Anyway [climbs down off soapbox and packs it away] I was standing right there in the playgroup in the middle of the toddler melee, and the idea for Don’t Call Me Princess came to me, both the title and the final line:

The draft. (A breeze).

Life then got in the way, as life does. I finished writing and drawing my comprehensive choose-your-own-adventure manual of pregnancy, fertility and birth. I wrote and drew my surprisingly successful graphic biography of Rosa Luxemburg (surprising to me, that is). Got married, moved house, got married again (to the same person, just reversing the roles this time). Went to Calais, hung out with some refugees, wrote a book about that, hung out with some more refugees – they thought my wedding photos were hilarious. But I kept Don’t Call Me Princess on the back burner, and when a publisher approached me last year and asked if I had any ideas for children’s books, I replied “Yes. There is something.”

It took me three days to write Don’t Call Me Princess. I roughed out a 36-page book format, approximately plotted that I needed six princesses, ruled out Cinderella (she’s not actually a princess), and cracked on with it. Just me, a three-quid plastic fountain pen and a subscription to a shit-hot online rhyming dictionary. (I confess, I did not match “Rapunzel” with “implausible” unaided). I had so much to say. I know it’s “just a story”, I know we’re “not meant to take this stuff seriously”, but traditional fairy tales teach some the littlest and most impressionable members of our society some deeply dodgy “romantic” ideals.

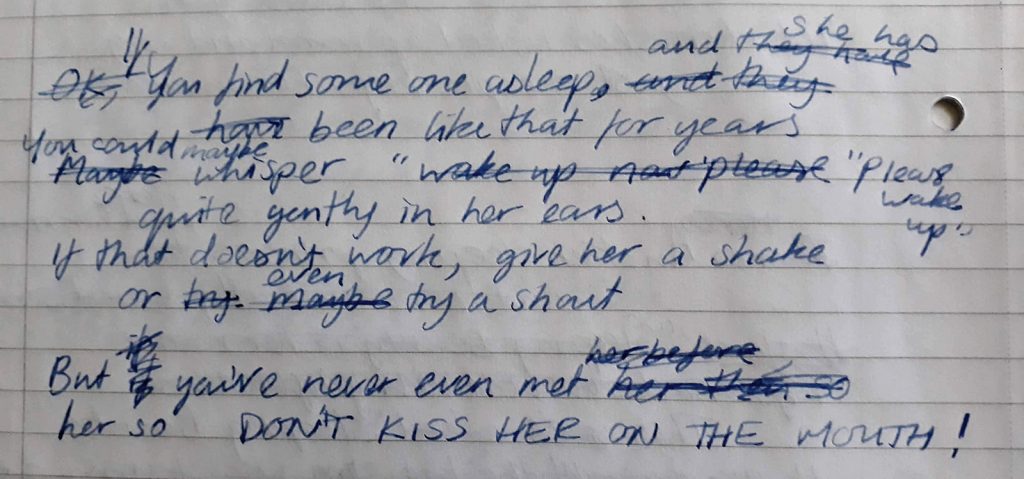

When that random Prince discovers a girl in a coma in bramble-filled castle, he definitely needs to rethink his next move…

What is it with this “Happy Ever After” scenario – rushing off with a guy who you’ve never laid eyes on before?

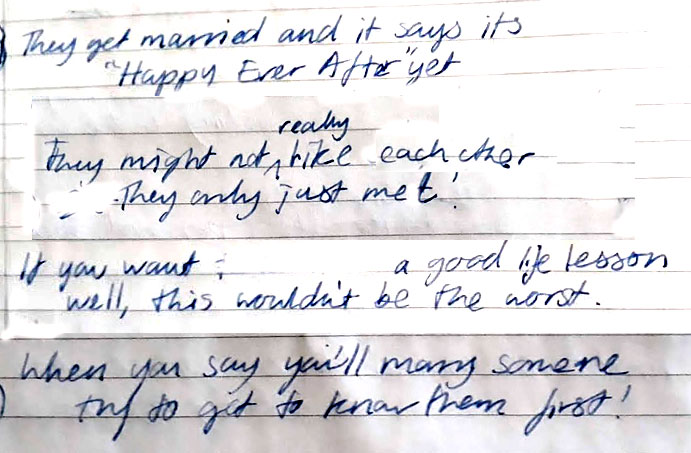

And Beauty, we’ve all been there, but please, learn from our mistakes and stop romanticising coercive control.

I read it to my daughter. Her eyes widened in surprise: “Did you mean for it to rhyme, Mummy?” (I showed her the online rhyming dictionary – I do not need to pretend to be cleverer than I actually am.) Until I read her Don’t Call Me Princess, my child was very fond of princesses. She did a complete 180-degree turn in her opinions after hearing the story once, which made her feminist mum incredibly happy. My daughter wants to be an Astronaut? She shall be.

People call me ‘Princess’ every time I wear a dress.

They ask me if I like it and expect me to say ‘yes’.

Why is it always ‘Princess’? What could they say instead

If they stopped looking at my body and they thought about my head?

Call me ‘Astronaut’ or ‘Journalist’ or ‘Brain Surgeon’ or ‘Teacher’

Or ‘Carpenter’ or ‘Pastry Chef’ or ‘Play Worker’ or ‘Preacher’.

Women do all kinds of things while wearing lovely clothes

But please, don’t call me Princess, cos I’m never one of those.

My mum is not a Queen, you see. My dad is not a King.

Instead of being a Princess… I can be ANYTHING!

Gratifyingly, my daughter and all her friends have taken to shouting the phrase “I can be ANYTHING!” at the top of their voices when I read them the story. I’m not sure it’ll work for a calming bedtime read.

The artwork. (A slog.)

“Great!” I thought. “Now to draw the book!” I had relatively recently drawn two 180-page graphic novels in less than nine months each. This was only thirty six pages. How hard could it be? I set aside a couple of months and launched myself into it. “It’ll be easy!” I thought. “No need to draw roughs. No need to develop character sketches. I know what I’m after!”

Dear, oh dear: it wasn’t and I didn’t.

Drawing for children is very very hard. I had never done it before, and I’d been annoyed, for years, at the assumption that I had. Cartoons are “just for kids”. People used to look at my graphic guide to climate change and say “it’ll be nice for children” and I wanted to shake them and say “No! Don’t give it to children! Give it to directors of petroleum corporations and members of the House of Lords!” But when faced with the reality that an unknown number of pre-literate people would be closely tracking my story purely through my pictures, they would be drinking in every detail with wide, uncritical eyes, it hit home pretty quickly that this artwork had to be exceptional.

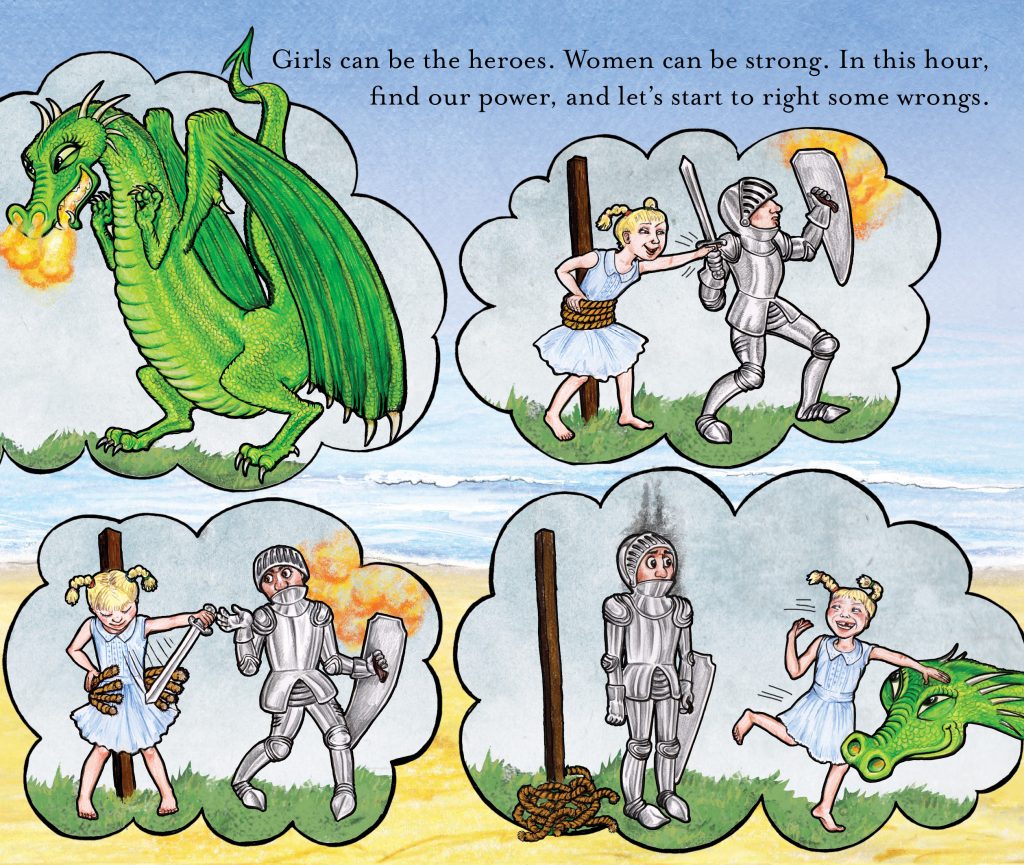

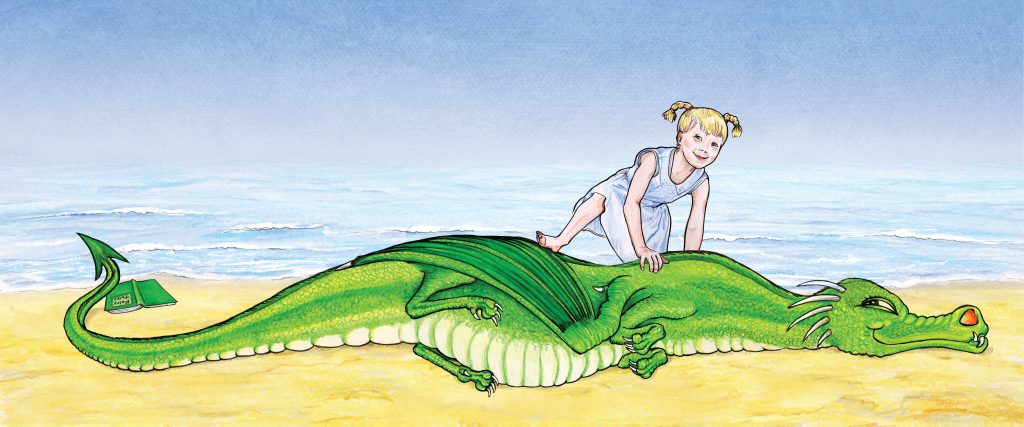

It was only thirty-six pages, except it wasn’t. I’d formulated a narrative of a child sitting reading fairy-tales on the beach while the action unfolded in thought bubbles above her head. And every detail of those thought bubbles had to be worked and reworked.

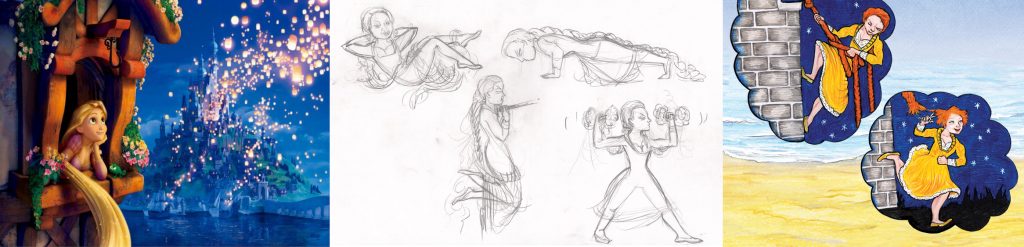

I’d decided early on to avoid Disney interpretations of the princesses. I didn’t want to attract any heat for copyright infringement, even though I might have been able to make a case for fair use by parody. But I also really enjoyed reimagining the princesses myself. Compare Disney’s Rapunzel with the Don’t Call Me Princess version:

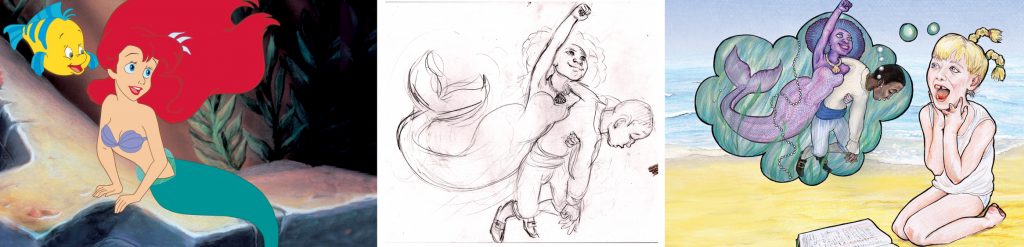

My Little Mermaid is considerably more righteous than her Disney counterpart:

It was fun, letting the princesses develop on the page, but I had a big problem with the central figure, the narrator. (I really shoulda done character sketches ahead of time!) I had always envisaged her as that little child standing in that blue dress at playgroup, but five years had passed since then, and my attempts to draw a two-year-old weren’t working. She seemed, clunky, uncanny, something unpleasantly lodged between reality and cuteness which was managing neither. I was three-quarters of the way through the book and the deadline was looming. I decided to go and see the renowned children’s illustrator Sarah McIntyre who chuckled a little at my presumption at thinking I could illustrate a children’s book in three months and very generously agreed to have a look at my pictures:

“Lose the Chuckie Doll” she said, brutally. She was right.

McIntyre explained that my narrator was lodged in the uncanny valley, and my attempts at realism weren’t helping her to come to life. She gave me a masterclass in how to draw child figures that really look cute, with smooth, artistic, stylised lines. I had a really hard think about what I wanted the central character to do and I realised that she needed to be more real, not less. This has to be a book about a real girl, reading a real book, in the real world, analysing the real princesses that we really should be critical of. And I have a child of exactly the right age. She’s seven. A good critical age. The perfect model.

So I went out and bought my daughter a princess dress. Oh, the irony!

I kept the little plaits from the original character. They’re cute.

It’s well past the deadline, but it’s done.

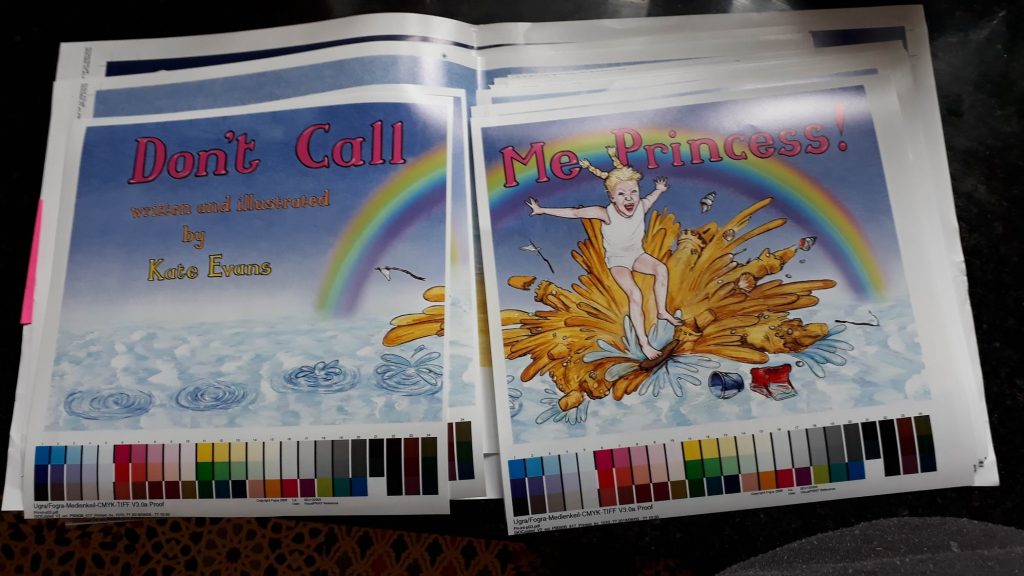

Don’t Call Me Princess is at the printer’s, [UPDATE: IT’S OUT NOW AND YOU CAN BUY IT!] the proofs looked delectable, and I have high hopes for it. If I’d written it ten years ago I would have been lucky to get a mention in the alternative press, but now there’s a real surge in awareness of women’s oppression and gender roles, maybe it’ll ride this new strong feminist wave? Maybe we can build something good here.

We’re currently part of the #MeToo generation. I’d like to raise the #DoesntHappenToUsAnyMore generation. Here’s how.

Don’t Call Me Princess will be published by New Internationalist in October 2018.

>>>>> BUY A SIGNED COPY BY CLICKING HERE <<<<<

Health concerns mean that the exciting launch events have been postponed until the new year.

Watch this space to find out more.

My daughter and I are both available for interview. Please use the contact form below for requests.

Thanks for reading. We hope you like it.

8 Comments on “Don’t Call Me Princess! – the backstory.”

I teach in Nursery at a primary school, and look forward to sharing this book with my children. I love their faces, when I read ‘The Paper Bag Princess’ and she tells Ronald that he me look like a prince but really he’s a bum! There are not enough books that challenge gender stereotypes at such an early age, and not enough teachers in Early Years acknowledge that this is a problem, the opening lines you quote from your book are spot on, girls especially in Nursery without uniform, are often told how pretty they look, as you say, like a princess. I tend to focus on how clever they are, how able, how skilful, how talented. Similarly boys are always asked to ‘do their muscles’ show how strong they are and I like to highlight their kindness, their ability to share. Children should be told they can be anything and they are who they are.

Rant over, look forward to reading it.

Mark

This looks amazing. We so badly need more children’s books that properly challenge gender stereotypes. Really looking forward to reading it with my son – and hoping there will be more!

Hi Kate, you’ve no reason to remember, but some years ago I placed a bulk order for your book about Calais refugees. They all sold and I was able to send a generous cheque to the organisers. I no longer run the charity (I’m 72 in July and disabled). My disability means that it is too painful for me to travel. Would it be possible to pre-order? She is 2 in July so by Christmas her mum and dad would be able to read it to her. I’m pretty sure she’ll enjoy your marvellous pictures and by reading it to her nice and early her parents will be able to pre-empt all the slush that will turn her brain to jelly!

I left out a line. The book is intended for my next door neighbours’ little girl. Sorry, brain failure.

My daughter is nearly eight but has global developmental delays that means most people would view her as being considerably younger. I hope she can grow up to be confident and less vulnerable than her condition seems to suggest. She’s heavily into princesses and dresses and your book looks a great way to change the narrative. I might have to get one for the grandparents, too, as they could do with a nudge away from the “isn’t she a sweet/pretty/proper little princess!” comments…

We’re sending you a bunch of extra stickers for her. Let’s reinforce that message!

We’re so happy with our copy – I just wish I could afford to buy copies for all the parents I know. This should be on the bookcase of every primary school/nursey/early years education provider.

DEAR KATE . I CONTACTED YOU SOME TIME AGO ABOUT GREENHAM .Never seen any of your books in our library. i had a very wild free childhood ,amazing grandmother brought me up to believe I could change the world.single handed !… mother a watered down version… My dad as i grew up sexism kicked in big time when i wanted to be an artist and travel the world. he wanted me marry the boy next door. Perhaps you have seen our family site http://www.birdchilfdsandgoldsmith.com some interesting poems included we have just completed all the footage for a film about greenham and banners that we made to unravel the vilification the of the gutter press. Its built around me and my daughter .The film makers were from chile and spain ..They met opn a filnm making course in CUBA…. im also taking part in a book about art/banners at Greenham .. there is a great poem on our website . inspired by my time as artist in residence in an international conference on sex role stero typing in Swansea in 1977 ..